What Limits to Religious Freedom?

- Academics

- Maleiha Malik King’s College London

- Peter Jones Newcastle University

- Public Figures

- Lisa Appignanesi President of English PEN

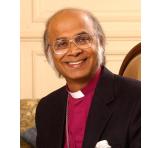

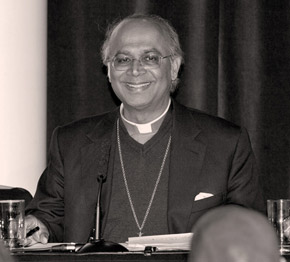

- Michael Nazir-Ali Bishop and Member of the House of Lords

- Julia Neuberger Senior Rabbi and Member of the House of Lords

Questions for debate

On the one hand, how much freedom should religious people and groups have to express their convictions? On the other hand, how much freedom should there be for others to express convictions which may be hostile or insulting to religion and religious people? In both cases, where do we draw the line, who decides and how?

Conclusions from the debate

There is a majority democratic consensus, expressed in part through legislation, which sets limits on religious (and secular) freedoms. Where religious expressions do not cross this line (e.g. display of religious symbols) freedom should be unrestricted. Where they do (e.g. refusing to conduct civil partnerships for gay couples), negotiation amongst the parties involved may be able to reach an accommodatiom or compromise. Mechanisms for such negotiation may need to be strengthened. There may also be cases where religious people can refuse to act against the democratic consensus on grounds of conscience, but there may be a price to be paid (e.g. those who cannot work on Sundays make up time elsewhere; conscientious objectors in war contribute in other ways).

Research Findings

The issue has come to a head recently because of a number of controversial rulings under new equality legislation in which the duty of equal treatment (especially on grounds of sexuality) has clashed with the exercise of religious freedom (e.g. when a Christian registrar refused to marry gay or lesbian couples on grounds of conservative Christian conscience).

The focus of religious freedom debates has shifted in the last decade from controversy over the right of Muslim women to veil to controversy over the right of Christians to display religious symbols and act (or refuse to act) on the grounds of their faith.

Controversy is currently being stoked by two extreme minority groups: aggressively secular groups on the one hand; aggressively conservative Christian groups on the other. The majority population, both religious and secular, is more ready to reach compromises and accommodations.

There are three separable issues in this debate:

- the freedom of religious individuals

- the freedom of religious groups

- free expression which may involve insult to religion

Cases being brought under Equality Law have to do with (A). Some exemptions from equality legislation have been granted to religious groups (B).

With regard to (A) the question is how far this freedom extends, and whether it ever gives grounds for not obeying a law, or flouting majority opinion and sensibility. What rights can be granted minority views, and who bears the cost of individuals or groups acting against a majority position on the grounds of conscience?

With regard to the freedom to insult religion (C), where insults do not amount to incitement to religious hatred, this can only be a matter of voluntary restraint rather than legislation. Recent cases of ‘censorship ‘ (e.g. closure of the play Beshti which insulted some Sikhs, or the Mayor of London’s refusal to allow Christian anti-gay advertising on buses) seem arbitrary (why not stop other things which insult e.g. ‘Jerry Springer the Opera’ which was insulting to Christians?) suggesting that the threat of public protest on the part of those who are ‘offended’ is more influential than consistently applied standards (e.g. respect for those whose deeply-held beliefs are being insulted).

"It’s often argued there should be accommodation of the religious conscience…We’ve already allowed some of the widest exemptions throughout the European Union from equality law … as a society we’ve reached an agreement about what the limits of that exemption should be, it’s represented by the Equality Act 2010."

Points of Debate and Disagreement

| Freedom of expression is in danger; religion is the threat |  |

Religious freedom is in danger; secularism is the threat |

| Equality legislation has already granted religion exemptions; the law is now settled and religious people must abide by it. |  |

That amounts to legal positivism; morality is a higher law and religious people must fight to change unjust legislation. |

| The law and society must make allowances for minority positions, even when they are unpalatable to the majority. |  |

Minorities must bear at least part of the cost of the majority’s toleration of their differences. |

Practical Suggestions

The issue of freedom is in danger of being hijacked by religious and secular extremes, both of whom claim to be oppressed by the other, and whose mutual opposition ramps up the dispute. News media often amplify such voices. There is a danger that equality law is hijacked by these extremes to make their point, rather than for its proper purpose (creating a fairer society).

Recourse to the law tends to amplify disputes rather than resolve them. Non-legal approaches and solutions are more valuable in this area.

In the face of this amplification of minority positions, it is important to remember and represent the fact that most religious and secular people are content to abide by democratic consensus and the law. It is also important to note that most issues of religious freedom are resolved at local level without recourse to the law.

More research on how such negotiation and accommodation takes place in workplaces, schools, public spaces and so on would be valuable.

More guidance about how controversial forms of religious expression can be discussed and negotiated would be helpful, especially in the face of current nervousness about religion and religious claims.

Whilst freedom of expression is important to a democractic and free society, it is useful to distinguish between different purposes and contexts. Academic freedom to pursue the truth, for example, must be safeguarded even when its result may offend, whereas the freedom to create an offensive artwork may not be as absolute, especially if its main purpose is to shock.

"Legal positivism can lead to totalitarianism and to a tyranny of the majority. It will not lead to that balancing of rights which we need today. Most conflicts in the last one hundred years have in fact been caused by totalitarian secular ideologies. In the past, including respect for conscience was part of law making, why is it not so now?"

How the Media Reported the Debate

"At least programme director Linda Woodhead speaks sense. Equality law and appeals to freedom are being hijacked by the aggressive fringes of religion and secularism to fight their ideological battles, she says."

"there are not two sets of people – Christians, or other people of faith, and those who are LGBT. There are LGBT Catholics, LGBT evangelicals, LGBT Muslims, LGBT Sikhs, LGBT Hindus, LGBT Jews, LGBT Buddhists, and more."

"He (Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali) held that religious and sexuality rights were not properly balanced and that the equality of persons should not be confused with equality of behaviour; that morality transcends the law…"